Reflections on Third Way Creative Leadership

Across four evening sessions in March 2025 I participated in the “Third Way Creative Leadership” course, led by Peter Weigold and hosted at Club Inégales. Each week, 7–10 participants came together to explore Peter’s approach to leadership of cross-form, musical improvisation through practical activity as well as explanation, analysis and questions. After each session I made use of Gibb’s reflective cycle to make contemporaneous notes which describe, analyse and evaluate my experiences and feelings throughout the process, as well as articulating follow up actions and areas for future development. To accompany the course, the sessions have been filmed and edited into a short documentary, in which some of the contributions I made have been featured.

The purpose of this blog post is to summarise and share themes from my contemporaneous reflections together with my reflections on the documentary and summative feedback shared with me by Peter after the course.

Theme one: working functionally as a tool for opening and processing awareness

Over the course of the four sessions, a theme emerged from a reflection at the end of the first session, where I had led a very short vocal and body percussion improvisation warm up activity. I had noticed how there were so many sources of information coming in from around the room, that it was difficult to process them and respond to them in real time: it felt overwhelming. As I documented in my journal that week, “it always felt very tentative — like my connection to holding and leading was always at risk of breaking down”. The volume of potential incoming information, the volume of potential options which are possible in response, and the ever changing nature of both, results in, what I experienced as, a stress response to a high pressure situation.

In session two, after leading a short musical improvisation where the group used instruments, I deepened my understanding of my own response to the challenge of being aware of and responding to so much musical information happening and developing in real time. In feedback from the group after my leadership contribution, it was observed that I had embodied the rhythm and pulse that I was looking to establish and hold within the emerging improvisation. I reflected in my journal afterways how this had been an instinctive response — to hold the rhythm in my own body, and to assert this in the room physically — which drew from my past experiences of leading group percussion workshops and performances with young people. At the time, Peter’s formative feedback was that I could have worked to establish the groove and pulse more securely in the room, from the musicians, rather than rely on my own, more instinctive reaction to hold it through my physical embodiment.

The instinctiveness of my own response to leading what I experienced as a high pressure situation was also mirrored in my observations of, and the reflections of, other participants in the sessions. Other participants shared that in their experiences of taking leadership roles they felt similar pressure and stress responses to my own. However, their own instinctive reactions which resulted from it were often very different. Some responded by leading through highly prescriptive instructions, some with more broad or general ones. Some responded by focusing on approaches they were more familiar with from their own practice: foregrounding vocal elements, for example. It suggests that there was something revelatory about the high pressure experience of leading this type of music: that the pressure of the experience reveals instinctive leadership qualities. I reflected at the time, that this understanding of what is instinctive, allows for areas of development to be identified: places where new tools, techniques and approaches are needed to be, not just learnt, but practiced so that they are readily and quickly accessible for deployment.

In week three a framework of instructions was introduced which provided ways of interpreting and shaping the unfolding musical improvisation. Peter offered three categories of instruction which can be used when inviting contributors to the improvisation:

Do this

Do something like this

Do what you like

In “do this” the instruction is precise and exact, and may need to be worked and refined with the contributor(s) before moving forward. On a spectrum of prescription, it is the most prescriptive instruction.

In “do something like this” there are constraints and parameters offered, within which the contributor has freedom to explore. The parameters may be musical in nature (notes, scales, rhythms, a tempo, a metre, etc). They may also suggest a function (to harmonise, to repeat, to solo, etc). They may be evocative of mood or emotion (melancholy, excitement, etc), movement, other sounds, or textures. They may draw from ideas already present in the music (mirror another player, harmonise a part, repeat a part, etc.) or they may bring in new ideas (ones from the leader, or others). They may be indicated by gesture (hand signals) or verbally. They may include a number of composite parameters (to play a melancholic bassline using C and D, for example).

In “do what you like” the instruction is least prescriptive and most open, being without constraint on the contributor.

As the group explored these three categories of instruction, the theme of functionality recurred: “do this” instructions (and the work needed to refine the music coming from them) provide an opportunity to develop key musical functions, particularly those required for “holding a center” (see theme two for further exploration of this); “do something like this” instructions provide the opportunity to add and shape musical functions to and within the unfolding improvisation. There are, of course, many types of musical function — Moore’s four functional layers are one such example within the world of popular music — and may include an element's purpose and prominence within the arrangement as well as its narrative or structural role.

Thinking and working functionally provides a way to filter and process the wealth of incoming information, and to respond to it with instructions which are more invitational, empowering and workable (qualities which are explored in theme three).

The metaphor I developed through the process was one of a mixing desk: the signal coming in was at such a high level, so “hot”, it felt like the meters were clipping (“in the red”). One way to resolve this, in the metaphorical situation of a mixing desk, would be to turn the gain down: to reduce sensitivity to sound, making headroom for the louder sounds, but also risking the loss of quieter sounds. To attempt to reduce one’s sensitivity to the incoming sets of information was clearly an insufficient solution: risking losing awareness of musical and creative ideas which are more nascent, quiet, vulnerable or hidden. What working functionally allows for is a filtering of the incoming information, rather than a reduction in sensitivity to it: it maintains an ability to have awareness of and respond to a higher volume of valuable incoming information.

Theme two: to explore the edges of something we hold the center of it

Peter describes “third way” leadership as being, “centred, led, grounded but open to the movement in, and from, every person present.” and that the leader is “open to change as each participant brings their unique voice.” He contrasts this with “first way” leadership — “where the ‘maestro’ makes all the decisions” and “second way” leadership — “shared collaboration”. In the “third way”, leadership is “not as top-down, but centre-out, holding the centre”.

Over the four sessions, we explored the concept of “holding the centre”: what it looks and feels like as an experience for the leader, and those being led. In my reflective journals, I noticed that it appears to exhibit itself in two key ways: both as a musical center, and a relational one.

Musically, we experienced how this “center” can be established in a number of ways: through a “backbone score” (containing a mixture of both “do this”, and “do something like this” type instructions); through functional instructions (“do something like this” type instructions, that may be verbal or gestural); through working with emerging ideas in the space. The intention is to find and “hold a centre around which you can spin an infinity of things”. In exploring a range of different centers, established and held by different leaders in the group, I noted that there were certain characteristics of centers which felt most enabling as a performer: they were invitational; they were stable; they were workable; they had a clear musical function; they balanced prescriptiveness and openness.

I noted in my experience of taking part in a number of improvisations as a participant over the four sessions that a strong musical center was enabling of, rather than prohibitive of, exploration of the extremity of musical ideas. When the musical center was weak, or unstable, or yet to be established, it was more difficult to engage with and participate in the improvisation. When the musical center was clear, solid, and stable, it was more possible to engage, participate, and contribute, even more extreme musical ideas, as they could be worked with and responded to in real time.

Inter-related with the musical center is the relational center which also needs to be held by the leader. From the very first session, this was demonstrated by Peter in the way he actively worked to open the space to a wide range of energy levels, very practically, through vocal warm ups which invited each participant to make use of a wide range of energy levels and types. Peter coached from a relational center which was both unafraid to welcome new ideas and contributions, as well as being confident to work and shape ideas and contributions to keep the group held together.

I noted in my reflections of the course, that both musically, and relationally, that an extremity of ideas and energies was made more possible by when a strong musical and relational center are established and held. It is worth noting that, as a leader, the job is to hold the centre, rather than “be” the center: just as the leader does not have to be the percussion and bass which may create a stable groove around which other players can contribute (a musical center), the leader does not have to be source of the relational qualities which are needed for a group to function. The center is facilitatory. Using the framework of instruction in theme one however (as one of many other leadership and coaching skills) the leader can establish and hold a center around which a vast extremity of energies can spin: the stronger the center is held, the greater the extremity of energy can allow to be spun.

Theme three: centered leadership utilises invitation as means of workable empowerment

Drawing from themes one and two, the third theme from my reflections is that centered leadership makes use of invitation as a means of workable empowerment. An invitational quality may be created in numerous ways — through the backbone score, through physical gesture, through verbal instructions, through the establishment of a musical groove or soundfield, and others — which each result in two desirable outcomes: workability – the resulting engagement, relationships and musical material being something which is capable of further work — and empowerment — that the others in the group are able enabled to contribute more fully.

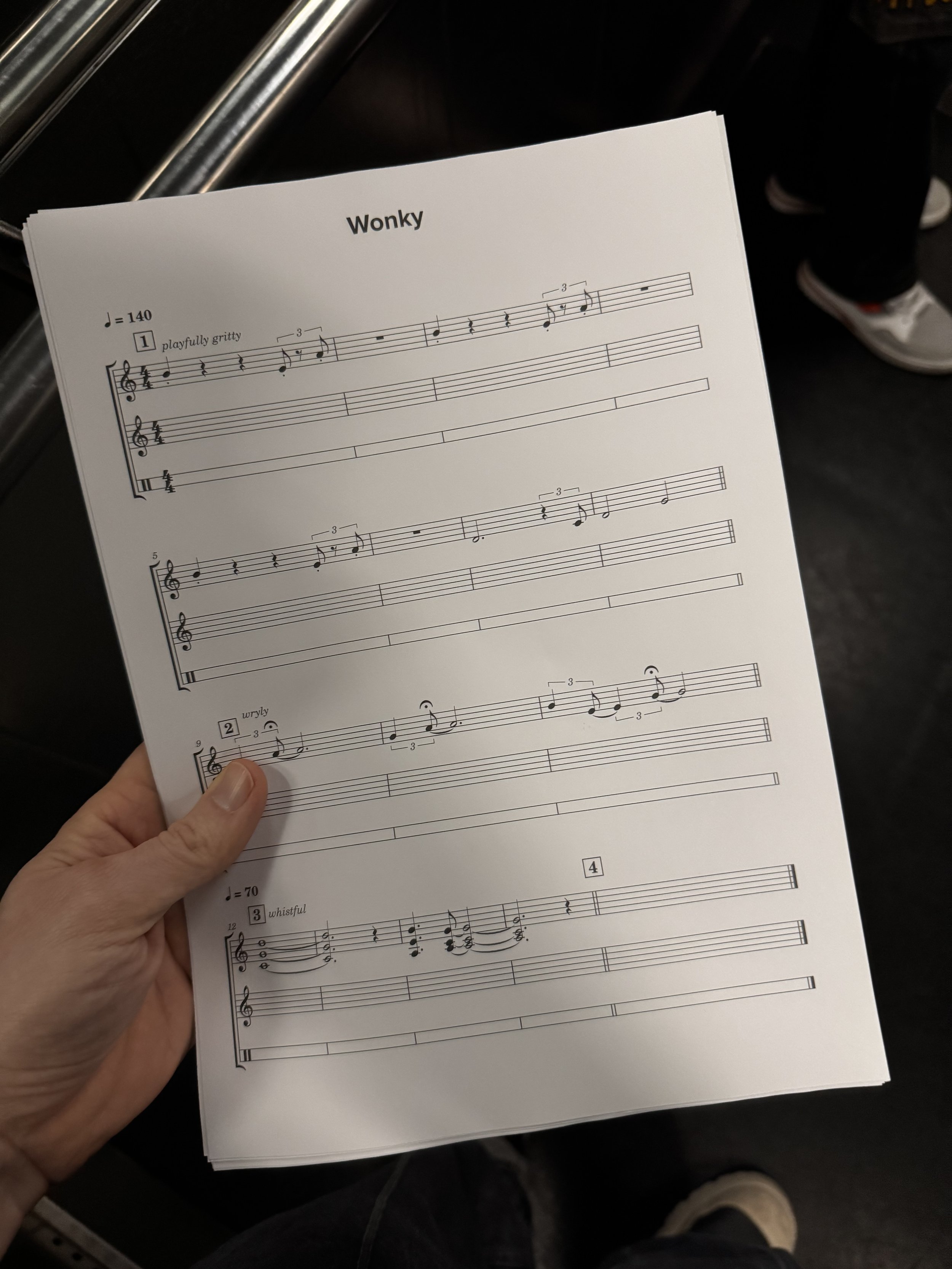

In developing my own one page score, to work from week four, I reflected strongly on the musical elements to include, and the instructions I would come prepared with, that I hoped would be invitational in nature. I met with Peter to discuss a draft score in the week before the fourth session, and refined some of the musical ideas, resulting in the piece, ‘Wonky’.

One thing that came up within the sessions, and within my reflections on them, was a mistaken belief that perhaps many of us held, at least in part, that empowerment was to be most deeply found in allowing people to do anything they wanted: a “do what you like” type instruction. However, throughout the four week course, it became clear that this was not the case. In fact, in some contexts, a “do what you like” instruction may be given, as a means of holding greater control, not less. Because when the leader is not clear what it is they are looking for, and simply asks for members of the group to do what they they like, as a means of finding it, the leader stands as the gatekeeper, selecting and rejecting what may result, rather than empowering contributions through a “yes, and…” approach. Because the work results from the group, not any one individual, then empowerment, empowerment that is workable in a group setting, comes as a result of setting up the conditions where each contribution is another link in a chain of “yes, and..s”.

This may require working to refine ideas — “do this” type instructions — this may require clarity of communication with a particular focus on the musical function that should be fulfilled — “do something like this” type instructions — and then making space for more free contribution within an established context — “do what you like” type instruction.

Within my score for ‘Wonky’, I looked to create opportunities for each of these approaches. In section one, I composed a short melodic groove with a strong rhythmic motif (including a turn around) which could be worked as a very specific idea in the room, and then built upon. In section two, I composed some rhythmic stabs which could be used to punctuate the piece, and create moments of pause and soundfield which may be the basis of further improvisation. And in section three, working with harmonic material — a chord sequence — to create both a sound and harmonic field that I hoped would be invitational of further contribution. Alongside the score, I made notes for myself of potential functional instructions to offer, mindful of the instrumental makeup of the group. In section one, this included requesting “palm muted strings” “long held notes” “vocal motifs” and “percussive grooves”. In section three, this included mid ground elements of arps and fingerpicking, as well as solo parts.

I shall reflect on some of the specific results of these approaches in the next section, as they feature within the documentary embedded below. But as a general reflection, not just on my own leadership, but in participating as others led activities in the group, I noticed how an invitational quality can feel elusive — I believe I know more now, about what can help to bring it about, but still do not feel as though I have a complete understanding of it and how it is produced — but is very visceral when it is present. I recall vividly, a moment when another participant was leading an improvisation in session three, and was making use of almost entirely “do this” type instructions. At the time, I found it very hard to be included, or to contribute. Within this however, there was a moment when two singers were interacting, and I felt, for the first time, that there was a musical idea that I could, and deeply wanted to, join in with: an invitational quality had emerged. The moment was very quickly interrupted by the leader, who had further “do this” instructions, and the invitational moment was gone. I learnt from that experience, to notice when an invitational quality is present, and to move with it, rather than against it.

Reflections on the documentary and my part within it

In the documentary, Peter summarises some of his key principles and ideas:

Presence. Presence is reflected in having feeling for the space; working with the energy of the room; being constantly observing; working with musical forms of coying, and call and response; developing accuracy and feel, engagement with the group and honouring each individual; embracing stillness and noticing the quality of it; establishing and giving permission for range.

Signals. Signals include hand gestures which are elemental and indicate a function or role, regardless of style; as well working on as a spectrum of invitation — do this, do something like this, do what you want; working at a pace which means that things happen “before the commenting mind begins”; invoking rather than describing; actively banking material which can be returned to through instruction later; watching for saturation, and bringing things back down to cleanse things; noticing the potency of ideas, and nuturing them; pairing technical and expressive instructions.

The liminal space. The liminal space is an alchemical space that has been set up where the music can go in two different directions, and both choices can work; establishing a facilitatory musical center around which ideas can spin., including their documentation in backbone scores.

Watching myself back in the documentary, and in discussion with Peter in formative feedback after the session, three things stood out to me as particularly successful in my leadership:

My physical presence. I move around the group, conducting with physicality and confidence, which is quite at odds with my reflections on the internal experience at the time: feeling very on the edge of my ability, with a lot of internal nervous energy, which is not shown externally. On reflection, this physical presence feels a key part of invoking an invitational quality which holds a relational center.

My performance projection. One of my reflections from earlier, shorter leadership experiences on the course was to be less afraid of working on an idea until it was held by the performers, rather than attempting to hold onto myself. Watching the documentary back, I can see myself doing this, and achieving success with it, Starting with a strong physical embodiment of the rhythm from section one, and then coaching the group to develop the accuracy and feel of it. The establishing of this groove was successfully invitational, building a musical center which was facilitatory. Additionally, the functional instructions which I gave to go with it, successfully establishing musical roles, layers and functions which worked to move the piece forward, but also, resulted in creative contributions of others which I could not have imagined or generated myself.

The use of poetic harmony. Section three is based around a series of chords, and there is a tangible change of energy in the room when they are played. They achieve a strong invitational quality which is reflected in the way many ideas emerged in the room spontaneously which were not ones I had planned in my notes on the score.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reflecting across the four sessions of the Third Way Creative Leadership course, three central themes have emerged that continue to shape my understanding and practice.

First, working functionally provided an important tool for managing the potentially overwhelming complexity of group improvisation. By focusing on musical function — whether rhythmic, harmonic, or textural — one can filter and respond to the multiplicity of incoming information with greater clarity and intention.

Second, the concept of holding the centre — both musically and relationally — is an essential element of effective creative leadership. A strong centre ensured the stability and coherence needed to facilitate and enable creative contributions, welcoming an extremity of creativity, energy and expression.

Third, that invitation is a key quality and tool in empowering leadership. Clear, functional and invocational instruction and invitations are more empowering of others, facilitating and enabling them to engage and contribute more meaningfully. Invitation is neither overly prescriptive, nor overly passivity — it is an active, skillful process of shaping the conditions for collaboration, and the discernment of knowing when to move with, and when to move in antidote to energies in the room.

Throughout this process, there are also some areas for further reflection, research and exploration which emerge: making use of additional theoretical frameworks to deepen my understanding of the way my leadership practice is contextualised; further exploration of the theme of “invitational” as a concept, including consideration of critical perspectives; and continuing to deepen my understanding of the application of the themes explored here through further practical application of skills in a wider variety of contexts. Additionally, my practice as an electronic musician sits alongside my practice as a creative leader, and was also developed throughout the course, and would be an area to return to for further reflective analysis.